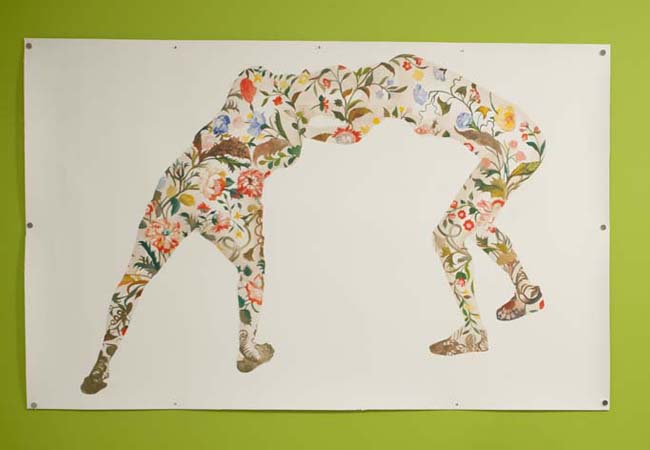

Firelei Báez, "Crewel" (from the series Prescribed Seduction); 2013; Guoache and ink on paper; 48 x 77 inches

Firelei Báez, "Crewel" (from the series Prescribed Seduction); 2013; Guoache and ink on paper; 48 x 77 inches

Approaching works of art from an emotional perspective, though usually frowned upon, is always rewarding. The artists that I have selected for inclusion in The Emo Show—Firelei Báez, Dahlia Elsayed, Antonia Pérez, Wanda Raimundi-Ortiz, and Edgar Serrano—all make works that explore a wealth of connections between viewer and idea, subject and interpretation, logic and emotion. Following the impulse of Rasa Theory, these works can all be thought of as ascribing to the basic tenets of humanism, and to suggesting a mental state related to the range of human emotions.

Beginning with the outlines of her own head, Firelei Báez has created a series of large-scale portrait silhouettes. Prevalent in all of the images are the artist’s piercing eyes that are always highlighted. This new series releases any further connection to reality by evoking psychedelic or tiedye patterning across the surface of the figure’s features, hair and neck. Despite their scale, their familiarity conjures the intimacy of the nineteenth century tradition of silhouette portraiture. In thinking about the significance of portraiture, she pays particular attention to the subject’s history, noting “the layered histories that make up individuals, and all the alternative possible selves that can emerge out of chance and choice.”

Working with texts and language, both Dahlia Elsayed and Wanda Raimundi-Ortiz tap into the emotional content that revolves around words: how they call up emotional responses, trigger memories or nostalgia. Dahlia Elsayed employs memory, text and mapping to connect time, place and personal reflections on both. Beginning with words, she attaches location and recalls time, creating a moment through which the viewer connects to the abstracted landscape. She notes: “Writing and painting are close processes for me, coming in part from my background in writing, as well as an interest in the relationship between language and image. For over a decade, I have been making paintings and installation that synthesize an internal and external experience of place, connecting the topographical with the psychological.”

This connection between language and image is also at the center of Wanda Raimundi-Ortiz’s work Los Machos de Mi Vida (The Men in My Life), which employs the familiar text of the telenovela, a soap opera of baroque sensibilities. In the story, the artist plays all of the roles, from the master of the hacienda, to his hapless trophy wife, to the maids that maintain the stately home in the tropics. Occupying a range of personalities from head macho to luscious mistress, the artist works the range of hormonally-charged characters and their respective gestures. She states: “I’ve made work about the folks we don’t see… the chambermaids in hotels or the inner city mother of three, I have built my artistic career by creating works that investigate notions of otherness.” The otherness of the television soap opera characters is reasserted here through the artist’s own body.

Edgar Serrano layers mass-produced postcards featuring works of art from museum gift shops with stickers, paint, found objects, fur, plastic, foam, wood, and fabric. These layered pieces enact new meanings above the image printed below. Botero, Rothko, Pollock and many others are all subjected to the same treatment in which the gesture serves as much to cover the original as to call attention to it. The dialogue is heard between the layers, between the lure of abstraction and the appeal of the mass produced, between the shrieks of popular culture and the staid murmur of the history of art as it is presented in encyclopedic institutions.

Antonia Pérez has worked with combining domestic objects like kitchen towels with particular movements from the history of art such as Abstract Expressionism. She explores similar relationships through her crocheted plastic bags, which she has used to suggest both the history of Minimalism and the domestic nuances of craft. Her ropes recall the rigor of Barnett Newman paintings or the verticality of Donald Judd. Also hinting at whimsy, they evoke a mythological connection between earth and sky and ask what we might encounter if we were to climb the ropes. The delight that can be brought to mind through the mundane is key to Antonia’s aesthetic philosophies: “Repurposing discarded matter, elevating what has been considered low to a high position, needlework, relating to the domestic, blurring boundaries between drawing, painting and sculpture, my body of work is evolving, merging these core interests with a deepening engagement with abstraction.”

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

Rocío Aranda-Alvarado has worked for the Museo del Barrio as a curator since 2009, helping curate its biennial, The (S) Files. In 2012, she was part of the curatorial team for Caribbean : Crossroads of the World at the Queens Museum of Art, El Museo del Barrio and The Studio Museum in Harlem, New York, 2012-2013.